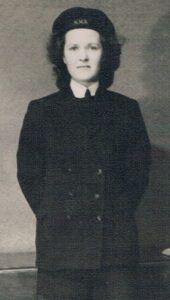

Doris Vera Ensoll (née Williams) 1923-2023

Doris Vera Ensoll (née Williams) 1923-2023

Mum wanted to do her bit for the war, and perhaps also to escape her duties as eldest daughter in a household of six (soon to be seven) siblings. Her parents ran a dairy near Gerrard’s Cross, Bucks. She chose the Wrens because the uniform was more attractive than that of the other armed services. I wonder if her application was successful because she could drive. Her Uncle had taught her so that she could pick up milk from local farms.

Mum trained at Mill Hill – presumably HMS Pembroke III on the certificate. We still have her notebook. She later said the Wren officers were marvellous people. They would have had to be, dealing with a corps of high-spirited 19 year-olds. My mother recalled cleaning an officer’s room with another girl, who dared her to try on the officer’s coat and hat; she accepted the dare, at which point the owner of the room returned: “Yes, you look very nice. Now take it off and get on with your work.” Mum said she felt about six inches high.

For those who ran the Navy, incorporating young women into an organisation bursting with young men must have been a matter for concern. Mum recalled a talk by “The smallest Admiral I have ever seen”, who adjured the assembled ratings to ” wear knickers closed at the knee.” Mum told me they found this very funny and had no idea what he was talking about.

Mum did undergo a driving test, with another girl. The vehicle was a three-ton Bedford lorry, with the engine by the driver’s side and the gear on top of the engine. The examiner was “a horrible man, who told us that if we failed we’d spend the rest of the war peeling potatoes.” The other girl went first, failed and was dismissed to the space behind the engine, where she blubbed audibly throughout Mum’s test. Mum passed, and joined the motor transport pool at HMS Foliot in South Devon, just outside Plymouth.

Mum’s duties included sorting and delivering the post round the fleet.

She recalled a confidential delivery to a battleship where she entered an enormous wardroom full of officers, who turned at her entrance. The PO with her apparently announced “Language, gentlemen! Ladies present!”.

On visiting a submarine she had to visit the ‘heads’, and a marine sentry was posted outside. She said that she was treated with utmost courtesy by the naval ratings. Her ‘hut’ at Foliot was a group of similarly aged girls, and they formed a deep attachment to each other; the last two on Mum’s Christmas list died in the last couple of years.

The matelots used to ask them to iron their collars when they went on shore leave.

As a driver, Mum did everything from driving officers to delivering prisoners. These were mostly ratings who had overstayed shore leave, and she’d buy them tea and a bun at a cafe whose name I have forgotten – the tea was served in jam jars. She also recalled driving Canadian troops to the docks for the disastrous Dieppe raid, from which most did not return. Later, driving American troops back to camp from Plymouth she heard a surprised call: “gee, there’s a dame driving this truck!”

Driving officers was a regular part of Mum’s duties. One of them ordered her to go to the pictures with him – an order she refused on the grounds that the vehicle might be stolen. He said he was rich enough to replace it several times over. Negotiating the delicate obstacle course of love must have taken up some time, with mum keeping a number of letters from admirers, men who were on active service and might be gone at any moment. Many pleaded for her photo, and they kept up a huge correspondence, partly to fill the endless dull shifts and partly to seek female contact in an all-male world. HMS Foliot was also the headquarters of ‘Combined Operations’, a special unit in which my father served as a Beach Commando RNVR. They met at a dance at Foliot.

They married in March 1946, against the advice of her parents, and she was discharged in May. For six years they lived a peripatetic life, Dad building his career in journalism, and mum becoming involved in politics. She had beer bottles thrown at her in Bishop Auckland, a mining area, for daring to suggest that the miners’ wives should vote as they pleased, not as their husbands instructed.

In 1952 they emigrated to Kenya after a job offer. Dad flew, at the expense of the company, leaving mum to make the trip by sea with a six-month old baby and dog! They were in Kenya for 18 years. With my father’s career doing well they often found themselves at national events, meeting everyone from Princess Margaret to Louis Armstrong. At the same time Mum kept house, built a family of three boys and beloved dogs, cats and horses. Her experience in the Navy taught her to “talk with crowds and keep her virtue, and walk with Kings nor lose the common touch”, while learning how to run a colonial household with servants.

Kenyan Independence meant fewer opportunities for the white settlers, and the family returned to the UK. Mum still kept a house for her adventuring sons when they needed refuge, but also built a career as a guide at Leeds Castle, where she worked for 20 years. The trustees found her a reliable and sociable worker, often calling on her to make up the numbers when they had important guests. Mum politely enquired about one American guest, who replied, “I’m in beans”. She was talking to the heiress to the Heinz fortune.

Mum was always building and maintaining friendships, including a reunion with the girls from hut 77 Foliot: “it was if not a day had passed”. She loved the Remembrance Day Service, often weeping at the thought of lives that had been lost. She became disabled in her 90s and increasingly constrained, but remained determinedly cheerful and created good relations with her carers, with whom she was ever popular. She also entertained them with an astonishing repertoire of songs, often from the war, not to mention advice on their domestic problems.

Noel Ensoll

Association of Wrens

Association of Wrens and the

Women of the Royal Naval Services

Bldg 1/87 Scott Road

HM Naval Base

Portsmouth, PO1 3LU

Registered Charity No. 257040

Support Us

You can help support the work of the Association of Wrens by making a donation.

Basket

© Copyright 2021 Association of Wrens - Privacy Policy Website developed by Foster & Scott